On May 2, 2021, the nation united to celebrate the first truly good news of the last miserable 15 months: Bennifer is back. But not like this. The cicadas have risen and low-rise jeans are haunting us. Nature, as they say, is healing. We’ve opened a portal to 2004 and we’re not looking back. Was it science or magic? Who knows! We don’t question the benevolent gossip gods.

And like the messy little gossipmongers we are, we’re wringing the content mill dry by revisiting some of our favorites from Jennifer Lopez’s canon. After all, she’s nothing if not a triple threat. First, Cate on the murky ethics of The Boy Next Door. Then, Zosha on watching Jennifer Lopez shine in Hustlers.

Cate on The Boy Next Door

Erotic thrillers are something of a speciality of mine, so I was drawn to JLo’s The Boy Next Door the second the trailers hit the internet back in 2014. A beautiful woman, seduced by an adult high schooler who tries to split up her marriage and ruin her life? I was down — if only for the complete and utter treat that is Ryan Guzman. Like most erotic thrillers these days, the movie isn’t particularly good, but it is enjoyable in a camp-aspiring sort of way. The most interesting thing about it though, is how much it ties itself up in knots to justify its own premise.

Lopez plays Claire, a high school teacher in the midst of a separation who has a one-night stand with her younger neighbor Noah. After she expresses regret over the incident and ceases contact, Noah develops a murderous obsession with her, risking her reputation and her family.

Now, teacher/student affairs are always a little icky to me, because I just don’t think the inherent power dynamic can be overcome except in very specific circumstances. (Feel free to date your driving instructor for example.) But Americans are absolutely obsessed with the “sexy teacher” fantasies of young boys, and over time, they've found lots of different ways to express that, despite the ethical issues that abound.

The Boy Next Door is a pre-Me Too film, but still feels acutely aware of the backwards argument it is making, and often strains credulity in order to align audience sympathies where needed. In fact, the story immediately sets Noah up as a violent manipulator who can’t be trusted. After their night of passion, Noah insists that Claire should leave her husband for good and run away with him. When she refuses, he insinuates himself deeper into her life, making overt public displays of affection, befriending her son and eventually threatening her with evidence of their tryst.

In the real world, the fault all lies with Claire. As the adult and the authority figure, it is her responsibility to not sleep with high school students, and the film demonstrates that it knows this by having her say as much when she breaks things off. But Claire is also our protagonist, and that means we need to be on her side. Rather than position her as someone who has erred, the film bends over backwards to explain why Noah is actually the villain.

Firstly, there’s a whole explanation for the fact that even though Noah is in high school, he’s actually already 20 because his parents moved around so much and he missed a lot of school. Then, when the two eventually have sex, Noah is the clear aggressor, repeatedly ignoring or rebuffing Claire’s requests for him to stop before giving in to passion. When she gently turns him down the next morning, Noah punches a wall. And when she firmly tells him that their inappropriate contact needs to end, he retaliates by pasting stills from a secretly filmed sex tape he made of them all over her classroom and threatening to release to her husband and the school. With each scene, his aggression escalates. He actively stalks her, and puts her family in danger by cutting the brake line on her husband’s car. Eventually, he murders her friend and ally (thanklessly played by golden-throated angel Kristen Chenoweth) and kidnaps her and her family in a fit of rage.

Now, the character described above is obviously dangerous and it’s reasonable for anyone in the audience to view him as a threat. But it occurred to me as I rewatched the film, that the characterization of a high school student as a dangerous sycophant driven mad by lust for an irresponsible teacher was itself part of the problem. Rather than focus on the way Claire put herself in a compromising position with a subordinate, the movie chooses to make Noah so over-the-top sociopathic that she becomes the victim by default. In fact, Noah was originally younger, but director Rob Cohen made the decision to age him up so that the audience wouldn’t lose sympathy for Claire. It’s one of the ways that the movie acknowledges the line it’s dancing on while pretending it hasn't crossed it.

It’s an interesting perspective to consider after the very different one presented in Hulu’s very good A Teacher late last year. In it, a female teacher exploits a schoolboy crush and spins it into an illicit, months-long affair. Years later, she has still not come to terms with the harm she caused her young victim, saddling him with the guilt and shame of her abuses. It’s not as “sexy” as an erotic thriller, but it is truer to life. Relational imbalances like those between teachers and students, especially when those students are not yet fully formed human beings, can leave them with psychological scars that take decades to heal. It’s glib and disrespectful to turn that dynamic into one in which the teacher is in fact the abused party.

The movie itself is serviceable enough in that the performances are engaging, the scripting is fairly tight and the tension is thrilling. There’s enough of a so-bad-it’s-good quality to make the film fun, and it’s immensely delightful to make fun of. Lopez channels the great work she did in the criminally underrated Enough and she brings the sincerity and desperation needed to sell the idea that she is being burdened by her own mistakes. But it’s Guzman’s Noah who is the real delight. He embraces the full bunny-boiling deliciousness of a Fatal Attraction in reverse, and plays to the rafters in every hormonal, roided-out scene. The campy flair of this film doesn’t work without his deliberate over-acting. His pissed-off snarls add some weight to Lopez’s increasingly dizzy desperation. The two play well off of each other, and despite the ethical quandaries detailed above, their singular sex scene does have quite a bit of heat.

I’ve never expected commercial thrillers to be fonts for moral clarity, and it is fun to watch characters quibble over ethical quandaries that are, in fact, quite cut and dry in real life. (See also, the immensely terrible Fatale, starring OSCAR WINNER HILARY SWANK for some reason). But The Boy Next Door isn’t something I can recommend in good conscience because simply put, it isn’t very good. That said, if you’ve got a free afternoon to kill and a bottle of wine to finish, this might be the late-afternoon film for you.

Zosha on Hustlers

When you watch Hustlers you are always watching Ramona. You’re not alone — everyone is watching Ramona, it’s part of her charm, her aura, her allure, her superpower. She struts out onstage in one of the best character entrances of all time and immediately everyone is rapt, as if there’s not a single other dancer in the club. She belongs to no single person, she’s an equal opportunity draw. No one is alone in bathing in her effect. No one, except, maybe, Dorothy.

Dorothy is always watching Ramona. She watches her react, manage, and run the room she’s in. Dorothy watches her when they’re out shopping, or when they’re working. Her loving gaze is always available if they’re together.

And why wouldn’t she — she is JLo after all. Hustlers marked a big waypoint in Lopez’s career, when an Oscar nomination seemed possible, even deserved. And to watch Hustlers is to audit the Lopez School of Movie Stardom. Like Ramona, Lopez has always seemed aware of her image, even if she toys with and experiences it with a bit of a sheepish shrug. The two share a sort of considered femininity, always on and making the impossible look easy, logical; it’s not backwards and in heels so much as rigidly planking off a pole and in platform heels.

Like other movies, Hustlers is a movie I had to be taught as I watched. I went in with one of my own best gals, in a theater full of women so teeming with excitement and fabulous outfits the only experience I can liken it to is a low-key Beyonce concert. And yet here was not the cathartic GirlBoss heist movie I expected, but a complicated, prolonged story about friendship breaking apart and blowing into the wind. There was crime and everything was too real. While it left me with a slightly more sour taste in my mouth than I expected, I found myself drawn to it, introducing it to people and deepening my appreciation for it every time.

And at the center of it all, every time, is JLo. Not just her entrance — although, my god, that entrance — but the way she ferreted it out facets of Ramona. She is so good in her role, so good at performing the Mama Bear/Older Sister/Cool Girl of the gang that I could, on early viewings, overlook the way she is filtered through someone else’s eyes. Everything about how we understand the story and the crimes within it is being modulated by JLo’s performance. It took multiple viewings to see that Ramona felt so whole not (just) because the writing was good but because JLo willed her to be.

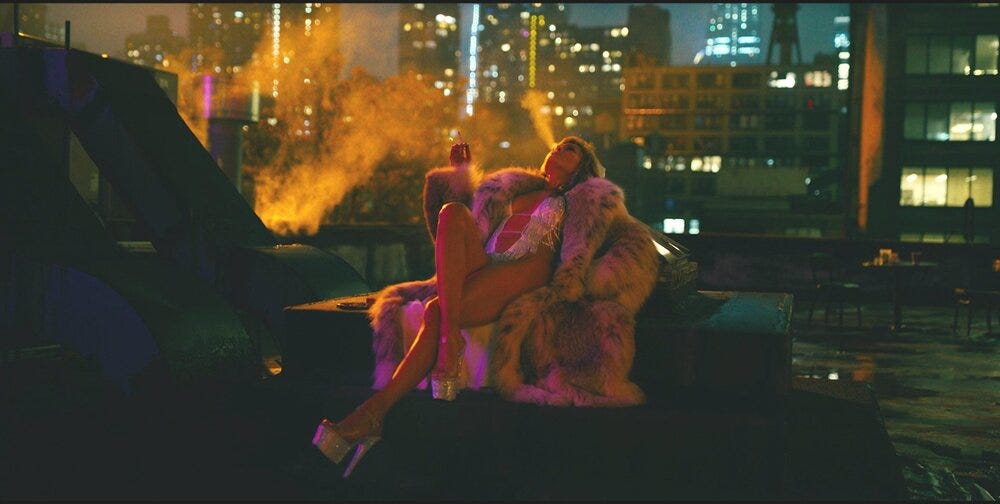

In the first scene Ramona and Dorothy talk, we are, once again, in the vantage point of Dorothy, taking in the picture (above!) of Ramona relaxing on the roof with a cigarette after a single song on the floor. What I know, what we know, watching these two characters now is how destructive the road ahead is for them. But in this moment we see something profoundly sweet.

Ramona is swamped in fur, generating luxury in every inch. As Dorothy concocts a reason to talk to her — she needs a light! — it’s possible to ignore, on the first screening, just how much Ramona is angling right back. In Hustlers Ramona is always on, and so it’s impossible to know where her hustle stops and her genuine warmth begins. But what we know for certain, sitting on the roof, is that no matter what these two women are thinking in that moment, there’s an ease to how the conversation flows between them. In a few breaths they move fluidly and together from support to slightly catty observations, to swapping war stories, to an invitation.

Memory is notoriously tricky, and an absolute gas to play around with in film. And yet, like so much in Hustlers and beyond, Jennifer Lopez makes it look easy. To compare to another movie I watched recently (such is the hazards of getting your reviews from a newsletter written anywhere from days to weeks in advance), The Manchurian Candidate, Lopez can carry the audience from a lady’s tea luncheon to a Communist brainwashing camp with a single line reading. I can’t say I have always been a fan of Lopez’s acting style, but with Hustlers it seems clear that maybe she just needed the right role to flaunt her true power.

Assorted Internet Detritus

CATE: An unconventional gay anthem, the girl-bossification of a madwoman, America’s drinking problem, on Whitney Houston’s two voices, on pro-choice road movies, Disney stars can have a little “fuck.” As a treat. And work won’t love you back.

ZOSHA: An in-depth reading/history lesson in the “Jenny from the Block” video. The end of the pandemic is about vibes. An intersection between Ted Lasso and Mare of Easttown. What Bowen Yang is doing for queer representation on SNL. What’s so scary about “birthing people” as a phrase. The dour, fluorescent history of office lighting.

Next week, it’s Cate’s birthday. We’ll be celebrating in style.

Zosha + Cate <3

twitter:@30FlirtyFilm

instagram:@30FlirtyFilm