Institutions are like huge ships. Even when they take immediate action, it still feels hard to believe they’ll ever change course. That idea of course, applies to everything from your local book club to the state of policing in America, but for now, we’ll start a little smaller.

This week, our selected films create a strange symmetry: tonally different but equally pressing reminders that changing an institution from the inside out can be some of the toughest work of all. First, Cate on Lean On Me, and the racist legacy of treated black and brown kids like a problem to solve. Then, Zosha on the dark themes and hallways lurking in The Power.

It’s almost time babes. Get your vaccine, prep your neglected corporeal meat sack. Hot girl summer approaches.

Cate on Lean on Me

One of the things I’ve realized now that I’m older is that a lot of my cinematic taste was shaped by my father. He had command of the family television, and so we watched what he watched. His preferences became mine, and the films he loved shaped the way I saw the world.

Lean On Me is one of the films I remember watching over and over with my father as a child. I loved it because he did, and I subscribed to the movie’s patriarchal model of education and discipline. In watching it for the first time as an adult, I finally recognize the film for the blatantly racist mess that it is.

In the film, radical teacher Joe Clark (Morgan Freeman) is ousted from his position at Eastside High— a white high school— in retaliation for his rabble-rousing. Years later, and importantly in his absence, the school’s demographics change. The student body is now predominantly Black and Latinx and the hallways are a dangerous place for both teachers and students. Dealers sell drugs out in the open, and fights regularly involve the threat of injury by knives or guns. It’s in this environment that Clark’s long-time colleague and friend seeks him out to return to Eastside as its principal in order to get the students’ standardized test scores up and prevent the school’s defunding and closure.

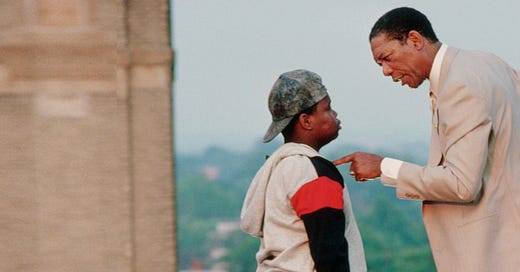

At the outset, it’s the basis for a fairly heartwarming tale of redemption. But instead, Clark (based on a real man with an identical reputation) barrels into Eastside like a bull in a china shop, berating and abusing the teachers and immediately expelling “problem” students on the thinking that they are bad seeds preventing the real students from learning. The mass exodus restores a semblance of order to the school (Clark orders that the heavily graffitied hallways and classrooms be cleaned) but Clark continues to wildly abuse both teachers and students, arbitrarily firing the former and publicly embarrassing the latter.

In the background are the political machinations of the mayor, who is prepping for reelection. Clark was installed on his instruction, but when Clark goes rogue by insulting the PTA president (he tells her that her son would not have been expelled if she wasn’t on welfare!) and chaining the school’s doors to keep drug dealers from slipping back in, they all but go to war.

Lean On Me was released in 1989, just five years out from the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, and Hillary Clinton’s infamous 1996 “super predator” remark. The views that this film reinforces are very much of a piece with the way the political winds were blowing at the time. The idea that as a whole, black students were an indistinguishable mass of dysfunction from whom the exceptional few must be saved was the conventional thinking of the time.

When Clark expels 300 or so students at the beginning of the film, no time is lent to considering what precisely would happen to them. Throngs of minority students from disadvantaged homes were cut off from one of the first stepping stones to a better life. But the fact that they were “disruptive” or otherwise unmanageable was seen as an inconvenience to Joe Clark’s Eastside High redemption narrative. In fact, in one scene, when one of the expelled students comes back to ask for a second chance, Clark takes him to the school’s roof and tells him to jump, because his drug use was only delaying the inevitable. The student was 14.

The real Joe Clark— and the one depicted in the film— reinforced the belief that black students, black children were beasts in need of a firm hand to tame them. No consideration is given to the home lives of the students, the circumstances they are battling against or the hurdles they have to overcome simply to make it to school every day in the first place. Rather than place the failure of their education at the overarching systems that should be held accountable, Clark lays the burden at the feet of the students themselves, and those of the teachers who are doing the best they can with criminally few resources.

It’s a position that earns his praise and adulation because he is a convenient stand-in for the fears and anxieties of a white audience paralyzed with fear at the prospect of their children interacting with those kids. (Look up the people involved in the production of this film. Spoiler alert: yes, they are.) But more insidiously, Joe Clark’s tough love philosophy plays into the pernicious respectability that plagues so many black communities— that discipline and assimilation with guarantees safety and success. It is white supremacy without white people, enacted on the psyches of children.

I used to love this movie. I saw Joe Clarke as a man who cared, and was firm in his demand that his students succeed. But the image that stood out to me across all the years was of Clark yelling at his black female vice-principal as she cowered before him. Because for whatever else he may have achieved, Clark was first and foremost a patriarchal tyrant and a bully. And black children deserve to be nurtured without fear.

Zosha on The Power

I do not think that The Power is quite as smart or powerful (oop) as it thinks it is. Set in 1970s London, we follow Val (Rose Williams), a trainee at an impoverished East London hospital. Like Val, the city is doing the best with what it can. In her case, it’s recovery from a traumatic incident in her youth we get flickers of. In the city’s, nightly blackouts ordered by the government to conserve power during a miner’s strike plunge the whole city in the dark — not something Val does well with. Still, she’s slotted into the night shift as punishment and is forced to not only monitor the ICU through the dark night but also deal with a wrathful ghost stalking the halls of the facility.

Right away a few things stand out in the film: the implied sexual assault themes that will cast a pall over Val’s life, the too-cute-by-a-half pun the title suggests to connect the themes of electricity and institutional silence. You can see the beats coming before they peek their heads around the corner, and the ending doesn’t do much to surprise. Of course, art is about more than just its predictability — it’s not about whether something happens but rather how it’s executed, elaborated, deepened by the way it plays out.

And this, I think, is where the main strengths of The Power play out. While the story can often be too slight for such weighty material, the image of Power is great. Even in the day, the hospital is a sickly green, at once comforting and nauseating; by night, it’s looming, shrouded in an unreal darkness and little-aided by the warm gas lamps carried around by the staff. Although the movie plays it a bit slow for my tastes with the initial haunting, every plunge into the supernatural brings a shudder and a gasp. Like an optical illusion, The Power understands how your brain can make sense of images flashed in front of your face before your mind can (if you follow me).

Ghostly showdowns are accompanied by not a sense of fear so much as dread — perhaps a double-edged sword, given how the themes are so profoundly sad as to overwhelm the story. It’s Williams who’s tasked with bridging the two worlds, literally, flitting between meek and menace with just an instantaneous shift in her face. The physicality she brings to Val is remarkable. Her performance filled in the gaps around our scant information of Val, imbuing the whole thing with more poignancy and range, even when she can’t give the story the depth I wanted from it.

And ultimately that’s what’s stuck with me most about the film in the days since I’ve seen it. Sure, I didn’t love it; a lot of the time I wasn’t scared so much as analytical of the things I was watching (a respectful response, I suppose, but not so much the visceral physical reaction one wants in a horror film). But even knowing what was coming, even feeling relatively reserved throughout, I still feel a pang of anxiety when I flick off the lights before bed. The final beat (no spoilers!) in the moment left me shrugging; eh, that wasn’t too bad. And now it echoes in every silent darkness beyond the doorway of my house.

Assorted Internet Detritus

CATE: It costs money to be a drag queen this fabulous, sounds like it might be better to skip Them, how Andy Cohen will reckon with a reality television franchise, how to prep for the return of your garbage self.

ZOSHA: What “restorative justice” can look like for the celebrity bloggers of nigh. Tracking the changing face of bubble tea as a Chinese American. The rise and rightful fall of pop star purity rings. Brenden Frasier is a perfect himbo. On Fran Lebowitz and the power of media.

Zosha + Cate <3

twitter:@30FlirtyFilm

instagram:@30FlirtyFilm