It's issue número dos, so you know the drill! It's the same as before: two complete film reviews written in 30 minutes or less. This week we're bringing you a reunion of sorts for The Devil Wears Prada with musings on Anne Hathaway's criminally underrated film Colossal from Zosha, and a meditation on Meryl Streep vis a vis Death Becomes Her from Cate.

Take this week's subtitle as warning or wisdom: "If You Don't Like These Actresses, These Movies Won't Change That." We have thoughts, to say the least. And as usual, there's a little of what we're reading to round things out. On with the show!

Zosha on Colossal

Written and Directed by: Nacho Vigalonda

Distributed by: Neon

At first I wasn't sure I was going to write about Colossal. I liked it, don't get me wrong! But I wasn't sure I had anything to really say about it; I appreciated its messages about toxic masculinity, and the value of picking yourself up from a bender and recognizing that your destructive behavior reaches beyond yourself. But that was about it.

But then I started reading about it. And over and over again people were referring to it as a charming sci-fi. Again, it is charming and smart. But... sci-fi? Let's review.

In the movie Gloria (Anne Hathaway) finds out that when she walks through a park at a certain time of day, a giant monster appears in Seoul and mimics her movements. While she might just be trudging through a playground on her way home from a bender, the monster is stomping its way through South Korea’s capital, laying waste to everything in its way. Eventually she learns that one other guy — Oscar (Jason Sudeikis) — also appears, only as a giant robot. He uses the power to hold her captive, promising to wreck the city if she doesn’t do and act exactly how he wants her to. Later on she remembers that he was always this way: When they were kids, her class project (a Seoul diorama!) blew into the then-construction site during a storm on their way to the school bus, and when he valiantly went to go rescue it, she saw him actually stomp it into the ground. Her rage channels lightning down from the sky, striking them both, and knocking his action figures — a monster and a robot — onto the ground.

OK so, board set, plot summary out of the way. Thanks for bearing with me; no one likes plot-heavy grafs, but it’s important for the discussion. Namely: At no point in the movie is this suggested to be the result of a scientific experiment gone wrong. We are never given an explanation about exactly why lightning slowly snakes to the top of Gloria’s head, but we believe it has something to do with the injustice she senses from Oscar. (There’s not even an attempt at technobabble, which is its own can of worms and should largely be left out; but I digress.) If anything, these elements are added into an otherwise mundane setting of her little suburb. The town is its own specific kind of Americana: the hometown you really hoped you’d never have to move back to, filled with exactly the same brand of jackass as when you left it.

The problem, perhaps, is that magical realism and sci-fi are two genres with the least defined boundaries. The former can mostly be described as elements of fantasy are woven into a story that is otherwise rooted in our own reality, as opposed to a wholly separate realm. Science fiction can be in an alternate world from our own, but is conservatively described as a type of fiction that is rooted in imagining scientific advancements. As genres, both have grown past these definitions, and both largely involve specific commentary on humanity and our own reality (“political,” but also usually just astute).

As you can see, the two are not not related in their aims. Likely, the reviewers who defined it as a sci-fi had their own reasons to do so — I would imagine it’s that a) there’s a big shiny robot fighting a monster in an Asian city, which feels like the sort of thing we’d default to sci-fi in a world where we have a lot of movies that involve big shiny robots packed with humans fighting for our safety. But also there’s b) They just don’t come from a culture where magical realism is generally practiced at much. It’s practiced all around the world (most prominently” in Latin American literature), but in the Western world — and the U.S. in particular — it’s not as common; it’s the “stuff of fables,” and hard to hold against notions of Western rationalism. Or, as this handy-dandy Wikipedia passage (30 minute time-limit, people) puts it:

Western confusion regarding magical realism is due to the "conception of the real" created in a magical realist text: rather than explain reality using natural or physical laws, as in typical Western texts, magical realist texts create a reality "in which the relation between incidents, characters, and setting could not be based upon or justified by their status within the physical world or their normal acceptance by bourgeois mentality."

Which is all to say, I get it; there’s something deeply American about believing that a woman and a man drunkenly fighting on a playground are controlling giant monster beings in a city around the world has a scientific explanation. In this moment in time I think we can all recognize that American blinders and search for any sort of rational to hold onto is a fierce mission.

But it also sort of ignores the interesting genre elements at play in the film. Yes, it’s got some compelling things to say about abuse, addiction, self-destruction, and nice-guy syndrome. It also has giant monsters, which are decidedly grabbed from the Japanese kaiju genre tradition. The name is Japanese for “strange creature” and can entail any number of things — think Godzilla and Pacific Rim, but also like Mechagodzilla, or the monsters that the Mighty Morphin' Power Rangers fight.

These monsters are representative of something — Godzilla, the king of monsters, famously is a stand-in for nuclear power and the dangers that come with it. Godzilla is a decades-spanning franchise, and in each iteration he wants something a little different; sometimes he doesn’t want at all, he’s merely there, neutral to our suffering or worship of him. Sometimes he’s created by mankind, sometimes he’s an old god whom our actions have awoken. What I’m saying is, he’s his own bit of genre bending. He is what we need him to be, and the best adaptations are the things that make good use of his abilities to be commentary.

In Colossal, the monsters are much more localized (aside from the round-the-world placement): They’re the everyday monsters we all battle, a personification of our worst impulses harming the greater world we live in. Knowing she has to be responsible enough to avoid the playground at 8:05 a.m., Gloria cleans up her act. Thousands of lives are on the line, after all.

Colossal has nothing good to say about the men in Gloria’s life; each one is ineffectual at best, and cruel at worst. But the movie seems to say that doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter if you have no one in your life who is willing to ask the best of you. Sometimes it’s enough to demand it of yourself, and know that that’s what you’re putting out into the universe.

Cate on Death Becomes Her

Written by: Martin Donovan and David Koepp

Directed by: Robert Zemeckis

Distributed by: Universal Pictures

Meryl Streep has been "Meryl Streep" for as long as I've been aware she existed, so when I discovered this film in my early teens, it was, at the time, a little like finding an old photograph of your parents—suddenly you realize that they had a whole life before you ever existed, and boy did they live it up when they had the chance.

I've grown up on daunting Meryl. Miranda Priestly is the role I most remember her for. Silver-haired and tight-lipped is the image that comes to mind when I think of the perpetual Oscar nominee. But Death Becomes Her has always been a welcome deviation in my conception of her, if only because the character she plays seems so beneath the dignity of the women she embodied in her later career, when I eventually came to know her.

I absolutely adore the idea of a Meryl Streep so vain that she drinks a magic potion that gives her amazing tits and an ass that won't quit. The dizzy, desperate energy of the way she portrays Madeline Ashton is so unlike the staid regality of say, her Julia Childs or Margaret Thatcher. But then again, if there's anything I should have learned from It's Complicated, Mamma Mia or even Florence Foster Jenkins it's that Meryl will 100% give you "dizzy bitch" if the role calls for it.

It's almost unthinkable to me that this movie bombed upon release in 1992, but I suppose back then they still weren't letting queer girls write about movies with any authority, so who could correct the record? But as a brand new baby queer, this movie has a certain... ineffable quality that telegraphs its queerness so forcefully that I can't help but be enamored. Madeline Ashton is GAY RIGHTS!

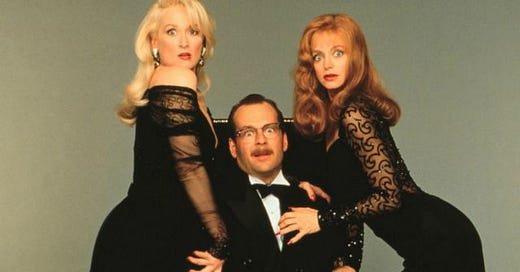

I focus this essay on Meryl not because she's the only one worth mentioning—seriously, why has Bruce Willis been stuck in action movies all this time—but because her performance is what creates for me an affinity with this film. As the rich, spoiled actress terrified of aging and desperate to turn back the clock, it's hilariously dark that she would achieve only a perverse version of her wish. Rather that remain forever young, she merely becomes immortal, destined to endlessly repair a badly decaying body alongside the equally vain Helen Sharp (Goldie Hawn). And isn't is wild how often movies conflate the two concepts? Why is no one ever satisfied to merely be smoking hot until the day they die? I don't know, and these two certainly couldn't tell me.

It's always amused me that what begins as a rivalry between these two women for the affections of a man ends in a lifelong partnership despite him. Bruce Willis' Dr. Ernest Menville is the weasely sort who never sets boundaries but resents you for breaching them. What either of the women ever saw in him is beyond me. But I've always loved when films recognize that men are incidental to a plot and then discard them. What we truly needed more of was Isabella Rossellini's aggressively enchanting sexuality. The only thing that would have made this movie gayer would have been for the former frenemies to team up against her in a display of total sexual dominance.

I've seen this movie maybe three times in my life, and each time I have a greater appreciated for the desperation of aging, vanity and rapidly escaping relevance. But there's still nothing quite like watching a trio of A-listers squabble and scratch until they can be confident they'll be the declared the fairest in all the land.

Assorted Internet Detritus

Zosha: One of my best friends passed along this awesome zine by Asian American writers all about feminism, care, history, and cultural context in the time of corona. It's been something I leave up in a tab and just keep returning to, whether I'm feeling particularly frustrated or disassociated from the current crisis. Also I'm trying to do my best to keep up with how brands are handling the pandemic, and anyone who seems to be mistreating employees ends up on my shit list! So I am glad to have this piece from Bitch about the smooth talking that is "ethical fashion" brands like Everlane (who laid off their employees not just in the middle of a pandemic, but unionization efforts! The nerve). In lighter news: May I suggest this quick piece on the rise and fall of mockumentary TV?

Cate: Because, like everyone else I'm bored at home but still messy and aching for drama, I've been amusing myself by reading transcribed posts from Reddit's infamous relationship forum. I don't usually read the forum itself, so I'm less familiar with its beats and rhythms, but I'm intimately familiar with the tone and textures of the posts that end up there before going viral on other platforms. This essay from Jezebel's Ashley Reese was an interesting perspective on what drives people to ask strangers to moderate their domestic disputes. I've also been thinking about how badly I want a proper manicure and, and how vain I feel for being so distracted by myself without one. Amanda Mull's essay in The Atlantic about the way we're clinging to routines of adornment during isolation was a comforting read, and it let me know that I'm not the only one feeling out of sorts without access to the things I use to make myself presentable to the world.

That's all we've got for you today. Next week we're celebrating, in a sense. For Issue #3: Eight Grade and Booksmart.

Believe it or not, we're still yelling about movies.

Zosha + Cate <3

Twitter: @30FlirtyFilm

Instagram: @30FlirtyFilm